by Amy Diaz

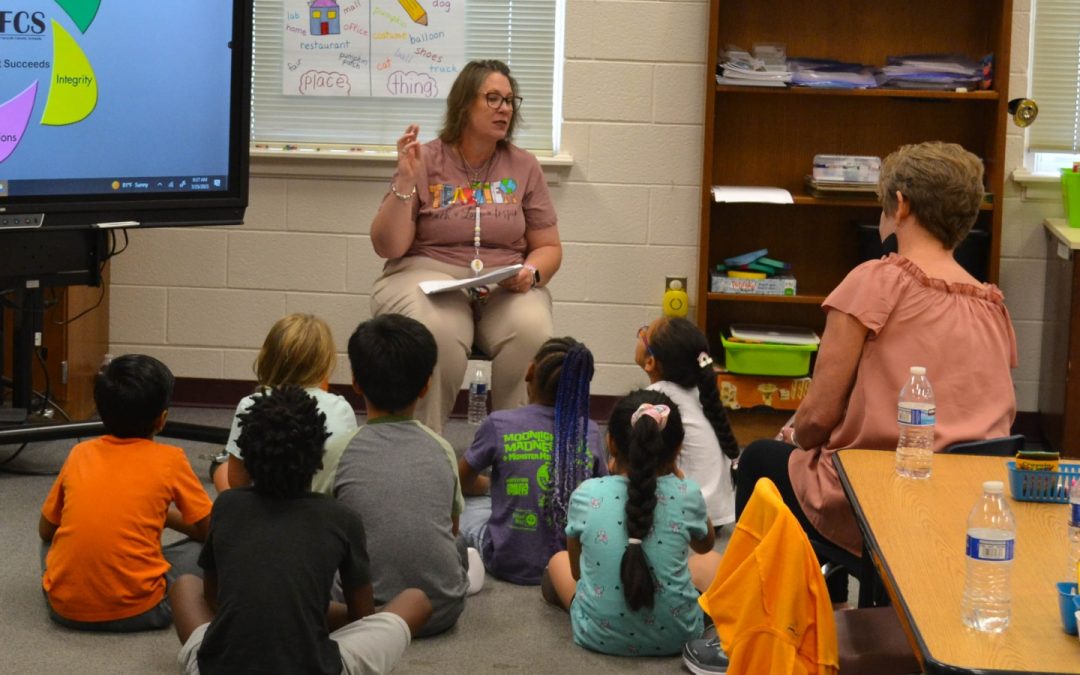

A handful of students gathered around their teacher during a morning lesson at Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools’ summer learning program.

Together, they sounded out the different pieces that make up words and used hand motions as they moved from one to the next. This is part of a curriculum called Heggerty, which takes a multi-sensory approach to literacy instruction.

WS/FCS Chief Academic Officer Paula Wilkins said it’s one of many tools the district has used over the last few years that aligns with the research around how a child’s brain learns to read.

She said students need explicit instruction to develop word recognition and language comprehension skills. That includes understanding syllables and sounds and spelling, as well as vocabulary and semantics.

“And so a lot of the science of reading is, use the right tools and processes, so kids learn and their brain processes in a way to make neural connections,” Wilkins said. “And get away from the practices that have not been effective.”

In 2021, North Carolina passed the Excellent Public Schools Act, which mandated instruction be aligned with the science of reading.

But to make that happen, teachers needed more in-depth training. The state provided school districts with access to a two-year professional learning program called Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling, or LETRS.

Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools was one of the first districts to participate, and completed the trainings this year. Wilkins said now the district is working to ensure that teachers are taking what they’ve learned into their classrooms.

“This is our path of what we are setting as a sustainable expectation to build knowledge and skills for people,” Wilkins said. “While we are also trying to work through challenges around curriculum alignment, around teacher support and practice, around continued professional development. And so that is, that’s the work.”

But that’s not all the work.

Wilkins started a Reading Warriors program a couple years ago that has trained community volunteers work with students. Principals are also doing Literacy for Leaders training so they can have a better understanding of what should be happening in their classrooms.

The ultimate goal of all of this is to get 90% of students reading on grade level by third grade by 2025. Third grade is important because that’s when students go from learning to read, to reading to learn.

“So for us, it is about moving on this trajectory without wavering because we know the research says 95% of students can read and meet grade level expectations for reading, but they need intentional, systematic, multi-sensory instruction,” Wilkins said.

But the district has a long way to go.

For years, about 50% of third grade students in the district were proficient in reading. Since the pandemic, that number has dipped down to about 40% which is lower than the statewide figure of 46%.

And it’s even worse for students of color.

Only about 26% of Black, Hispanic, and economically disadvantaged third grade students in the district are reading on grade level, compared to 63% of white students.

Esharan Monroe-Johnson is the executive director of Read Write Spell, a local organization working to improve literacy in the county and address those disparities.

“I think, looking at the numbers, when we disaggregate the data, really prompts us to think about, OK, what else do we need to do here to ensure that we’re raising the literacy rates in the community,” she said. “But also paying attention to that gap?”

She said there are a number of factors contributing to what she calls a literacy crisis in the county, and in the country. One of them is related to the kind of training educators are getting around reading instruction, but Monroe-Johnson is also thinking about the years before a child gets to school.

“What’s happening from birth to kindergarten to really support students in being ready for kindergarten?” she asked. “Are students in a language-rich environment that is developing their oral language skills, which are the prerequisite to being able to read?”

Those skills might come from a high-quality Pre-K program, but in Forsyth County, many children don’t have access to that. And for economically disadvantaged students and students of color, she says there are additional systemic issues that contribute to gaps in achievement.

“There’s issues with housing, there’s issues with the justice system, issues with employment, there are huge wealth gaps in our society,” Monroe-Johnson said. “So all of these things kind of come together to impact what happens at that third grade reading test.”

She said all of this means literacy can’t be an issue that the schools deal with on their own, and that the community needs to consider how to begin supporting students at birth– not for better test scores in third grade, but for a better chance at success as adults.